Building a Safe and Healthy Environment Amongst Complex Issues

If your family has suffered trauma such as domestic violence or child abuse (emotional, physical, sexual), parenting issues become more complex and difficult. This section introduces some basic concepts, but is not a substitute for professional support and help.

- Help the parent (you) be safe and healthy

- Learn how to how to provide an emotionally supportive environment for your child

- Routine, relaxation and recreation with your child

Help the parent (you) be safe and healthy

In order to build a safe and healthy environment for your child(ren), it is important to attend to your own emotional health, and develop a healthy support system for yourself that allows you to build a foundation for your children’s emotional and physical security and well-being.

Attend to your own emotional health and healing. Family trauma such as domestic violence may affect your mental health, showing up as symptoms of anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder. This emotional response may in turn affect your ability to respond to your children’s needs. Feeling overwhelmed by anxiety or depression for instance, may make it hard for you to appropriately respond to your children’s emotional distress, and their need to feeling safe and nurtured.1

Select with care the individuals with whom you share your time and emotional life. If you are not aware of your patterns in relationships, it is very likely that you will inadvertently become involved with people whose unhealthy emotional lives parallel ones that brought you and your children pain and suffering in former relationships. Resources for identifying unhealthy ways of relating to others include Co-Dependent No More by Melodie Beattie,2 and Keeping the Love You Find by Harvelle Hendrix.3 Additionally, Hold Me Tight by Sue Johnson4 and Seven Principles of Making Marriage Work by John Gottman5 can help you understand better the unhealthy relationships of your past, avoid such relationships in the future, and prepare for and build healthy relationships when you are ready to do so.

Make getting rest, nutrition, and other healthy practices a priority in your life. In doing so, you will both fortify yourself for the demanding work of parenting children whose lives have been deeply affected by trauma and model healthy self-care for them.

Learn how to how to provide an emotionally supportive environment for your child

The following points are paraphrased from an article by Bruce Perry, M.D., PhD, founder of the Child Trauma Academy, internationally acclaimed for his research on children who have experienced trauma and brain development.6

Talking about the traumatic event. It is not helpful to try to keep children from thinking about their trauma, and they will not initiate discussion about it with a parent or other caretaker whom they sense is distressed about it. Don’t ask the child about it. However, when the child does talk about it, don’t avoid talking about it with them. Listen without over-reacting, answer any questions they bring up, and be comforting and supportive.

Have consistency and predictability in patterns of daily life. Have routines that are predictable for the child. If the day is different in some way than the established patterns (rearranged schedule, a change in activities, etc.), let the child know ahead of time, and tell them why there is a change. It is very important for children who have experienced trauma to know that the adult in charge really has things under control Of course, you as a parent cannot be perfect, but when you are feeling anxious or overwhelmed, explain to the child why, help them understand that this is normal, and that you will get through it.

Nurture and provide comfort and affection, taking your cues from the child. “For children traumatized by physical or sexual abuse, intimacy is often associated with confusion, pain, fear, and abandonment.” Let the child initiate touch that is appropriate when they feel comfortable with it. Don’t demand, command, or grab and hold them when unexpectedly, or interrupt their play for hugs or other touch. Telling them to kiss or hug you can reinforce traumatic associations between power and intimacy.

Talk with the child about what behavior is expected from them, and what they can expect from you in response. Rules and consequences for breaking them need to be clearly communicated. Be certain that the child understands what you want them to do and not do, and how you will respond if their behavior is out of line with the rules. In using consequences, be consistent, but flexible when appropriate. Flexibility demonstrates proper use of reason and shows understanding. Physical punishment should not be used, and positive consequences should be the emphasized.

Talk about the child’s world. Help children understand their world by talking with them about it, and explaining things to them on a level that is appropriate to their age and development. It is reassuring to a child to be helped to understand how the adult world works. Children whose world is unpredictable and unintelligible will show signs such as sleep disturbance, mood problems, anxiety, fear, aggression, and excessively physical activity. When children do not have information that is based on facts, they will make up the difference between the unknown and a and their need to know what is going on. Be truthful about what is happening, being respectful of the level of information that is appropriate and safe for them to know, even when it is hard for you and or them emotionally. It’s okay not to know everything; if you don’t, be honest about that. In order to develop trust child needs you to be open and honest.

Be alert “for signs of re-enactment (e.g., in play, drawing, behaviors), avoidance (e.g., being withdrawn, daydreaming, avoiding other children) and physiological hyper-reactivity (e.g., anxiety, sleep problems, behavioral impulsivity).” During the acute post-traumatic period, all children who have been traumatized will display some of these behaviors or signs, and these can often be observed for years following the event. These become visible mostly following an incident of thought that reminds the child of the traumatic event. It is common for these symptoms to ebb and flow, without any obvious explanation. What you can do is write down what you observe, and try to identify behavioral patterns.

“Protect the child.” If you become aware of your child being upset in a way that indicates re-traumatization, stop the activity that seems to be distressing. Being aware of types of situations, activities, media (movies, TV programs, etc.)which seem to precede an increase in the trauma symptoms, and try to avoid, limit, or change these activities.

Provide opportunities for choice and a sense of control. Trauma symptoms will increase when a child feels powerless in a situation. When engaging in an interaction or activity with a child, offering some choices in that situation will help the child feel some appropriate power, and will help them feel more secure. This will enable more mature emotional responses, thoughts, and actions. The way you present consequences can make all the difference. Perry suggests, “You have a choice; you can choose to do what I have asked or you can choose something else, which you know is…” (the consequence already known to the child). Presenting the situation in this way can provide the child with the needed sense of power, and thus reduce their feelings of anxiety in such situations.

“If you have questions, ask for help. These brief guidelines can only give you a broad framework for working with a traumatized child. Knowledge is power; the more informed you are, the more you understand the child, the better you can provide them with the support, nurturance and guidance they need.”

On how caring adults can make a difference, Bruce Perry states, “The hallmarks of the transforming therapeutic interaction are safety, predictability, and nurturance. The most ‘therapeutic’ interactions often come from people who have no training (or interest) in psychological or psychiatric labels, theories, treatments and the adult expectations of the child that go with these. In interacting with the child, respect, humor and flexibility can allow the child to be valued as what they are”.7Emotion Coaching Parenting: The following is from John Gottman’s book, Raising an Emotionally Intelligent Child (p. 24). This book helps parents learn how to validate their children’s emotional experience, help them learn to regulate their emotions, and to generate and develop solutions to their own problems.8

- Become aware of the child’s emotion;

- Recognize it as an opportunity for intimacy and teaching;

- Listen empathetically, validating the child’s feelings;

- Help the child find words to label the emotion he is having; and

- Set limits while exploring strategies to solve the problem at hand.

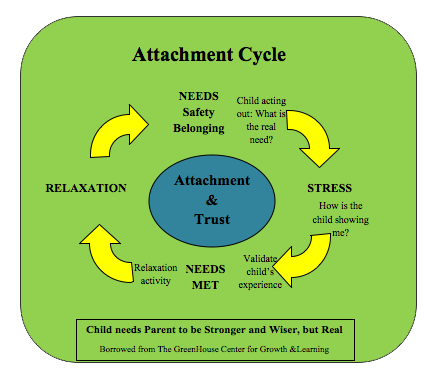

Children need adults who are stronger, wiser, and kind, but real.9 The attachment cycle below shows healthy ways of responding to the child’s stressors.

NEEDS: When a child is experiencing a need, the wise parent is seeks to identify the real need. For example, a child whining for a cookie or a toy, may really need attention and to be understood or a nap.

STRESS: Notice how the child is showing you his/her need (attention-getting behavior, fighting, etc.).

NEEDS MET: Validate the child’s emotional experience (You really want me to know how angry, sad, frustrated, etc. you are). If something traumatic has just occurred, parent needs to acknowledge the event, the feelings the child is having, and talk about what they can and can’t change. Express commitment to the child and family needs, and then follow through.

RELAXATION: Be with the child and reinforce sense of stability and connection through predictable routines and shared activities of working, playing, and relaxing together.

Routine, Relaxation, & Recreation

As described above, your child(ren) need their lives to be as predictable as possible. They need you to take care of yourself, and to be able and willing to respond to their needs in predictable, loving ways. Modeling healthy, honest responses to stressor is critical. They also need to you to engage with them in ways that are relaxing and recreational. Let them tell you what things feel that way to them, and then together, decide how to do those things together that meet that need. Here are some ideas to get you started:

| Read togetherDraw or color togetherPlay ball or frisbeePlay a board or card gameRide bikes togetherGo to the park to play

Watch clouds or stars Watch a sunset or sunrise together Take pictures together |

Make greeting cards togetherDo other craftsCub Scout, girl/boy scout requirementsSing to or with your childPut on music and dancing togetherCook a favorite meal new recipe together

Bake a favorite treat Take treats to a friend or grandparent as a gift Make up silly stories |

Recommended Books

Parenting the Hurt Child by Keck & Kupecky

The Whole Brained Child by Dan Seigel and Tina Payne Bryson

Raising an Emotionally Intelligent Child by John Gottman & Joan DeClaire

Hold Me Tight by Sue Johnson

Codependent No More by Melodie Beattie

Keeping the Love You Find by Harvelle Hendrix

The Seven Principles for Making Marriage Work by John Gottman & Nan Silver

A special thank you to Elsebeth Green of The GreenHouse Center for Growth and Learning for providing suggestions for excellent resources and for her gracious assistance in distilling an essential framework for this section.

References

1See Banyard, V. L., Englund, D. W., & Rozelle, D. (2001). Parenting the traumatized child: Attending to the needs of nonoffending caregivers of traumatized children. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 38(1), 74-87.

2Beattie, M. (1987). Codependent no more: How to stop controlling others and start caring for yourself. New York, NY: Harper/Hazelden.

3Hendrix, H. (1992). Keeping the love you find: A personal guide. New York, NY: Pocket Books.

4Johnson, S. (2008). Hold me tight: Seven conversations for a lifetime of love. New York, NY: Little, Brown, & Company.

5Gottman, J., & Silver, N. (1999). The seven principles for making marriage work. New York, NY: Crown Publishers, Inc.

6Perry, B. D. Principles of working with traumatized children. Retrieved from: http://teacher.scholastic.com/ professional/bruceperry / working_children.htm

7Perry, B. D. Understanding and Treating Traumatized and Maltreated Children: The core concepts. Retrieved from Feb 20, 2010 from: http://www.lfcc.on.ca/Perry_Core_Concepts_Violence_and_Childhood.pdf

8Gottman, J., & DeClaire, J. (1997). Raising an emotionally intelligent child. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster Paperbacks.

9Perry, B. D. Principles of working with traumatized children. Retrieved from: http://teacher.scholastic.com/ professional/bruceperry / working_children.htm